What’s Rome Got to Do with It?

Several years ago, after my class 5/6 had completed their performance of a Roman history themed play, a local indigenous parent at Escuela Caracol asked me, «Why are our children even studying Roman history? It feels so foreign and remote from our Mayan culture, and its legacy of conquest is such an ugly stain on the Americas. What does Rome really have to do with us anyway?» I contended that one could not fully understand our modern globalized world without some knowledge of and feeling for Ancient Rome. I also pointed out that he himself is a member of the (Roman) Catholic Church. It was a healthy interchange that left a lasting impression on me of the critical importance of bringing such historical studies into living conversation with our local Mayan context.

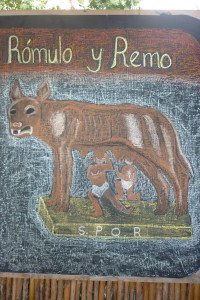

At the start of this year, our current sixth grade teacher, Diego Sacach Mendoza, approached me for help in planning his first block of the year: Ancient Rome. He was enthused and energetic to learn more about this subject and bring it to his class of all indigenous students. So we started at the beginning, with the founding myth of Rome: Romulus and Remus. These two boys, fathered by Mars and raised by a she-wolf, eventually decide to lay claim to their respective territories. Romulus builds a wall to keep out uninvited guests, Remus flaunts his disrespect for this wall by jumping over it, Romulus slays his brother Remus, and thus Rome is founded.

Diego stopped me there. When he was a child, he said, there were no walls whatsoever in San Marcos. People had lands that they cultivated and took care of, but no one ever put up walls — neither around fields nor houses. The walls, he said, began when outsiders came and settled. It was the first thing they would build. I told Diego to run with that thought — and he did.

After telling his class about these Roman brothers, they took a walk back in the mountain where someone had recently bought land. The

students observed that the first thing the owner had done was to clear the land and put up a wall. We have so much stone here that dry stone walls are the most common method. Some students love to play and experiment with stone building at school. The next day in class, the students discussed the nature and purpose of such walls. How are they built? Why are they built? What is their function? Do they work? One student said that her grandfather told stories about a time when there were no walls in San Marcos. So Diego gave them all the assignment to go home and investigate with their parents and grandparents what San Marcos was like when they were kids.

The next day they shared their research together. They learned that there was a time before walls in San Marcos. They shared stories of adventure when kids could run freely across all the land of San Marcos. They also heard that people did in fact deal with thieves during those days. So Diego decided to organize a class debate, with one side arguing for and the other against the necessity of walls.

Sixth grade is about meeting and observing the physical, concrete

world directly, and then moving those observations into the newly budding world of thought. The stone wall of Rome proved to be a perfect topic. The experience was energetic and challenging for the students, and it raised more questions than answers. The question of walls is perennial. It is at once practical, philosophical (do «good fences make good neighbors»?) and even geopolitical (the Great Wall of China, Hadrian’s Wall, the Berlin Wall, the current talk of a US/Mexico wall).

Perhaps most importantly for our context, the question of walls touches on the question of Maya and non-Maya integration in our community, and this difficult, delicate and poignant question is at the heart of our work at Escuela Caracol.